Is there anyone else about to read this, as fascinated as I am by simulations? A simulation of a game, weather, aerodynamic behavior, or any other action, has intrinsically the same goal - take a peek into the future and see how things will perform in real life.

These simulations all require an extent of calculations and variables to take into account, but also a model that will elegantly run through them.

"Aren't you describing Machine Learning? Isn't it also predicting the future with complicated maths and a model that no one really understands?", you ask. Yeah, I guess that ML fits into this description, but that's not the kind of predictions that I will be writing here.

As an Engineer, I like to think that I build things. Some digital, some physical. Some work, some don't. So, for this problem, I'll use a carpentry workshop as my example (because, you know, carpenters build things that mostly work).

Let's say that in our imaginary carpentry we have the following working stations:

- Cut wood

- Polish wood

- Paint wood

- Varnish and protective coating

- Assembly

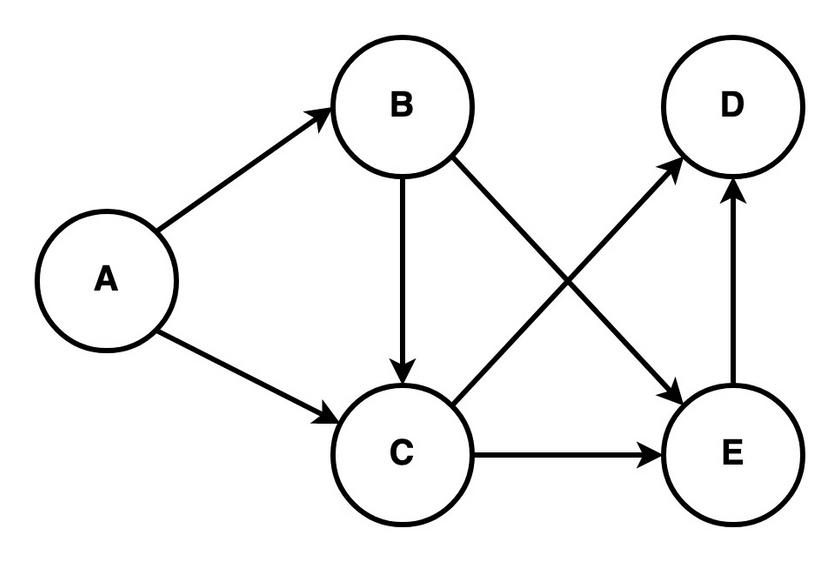

In this workshop, not all orders have the same processing. A chair may not need a painting or protective coating, but a kitchen table might. Or it can be a supplier for that Swedish company that doesn't assemble their products cough cough. Also, a given workstation can receive orders from various different stations. Imagine a directed graph like the one below:

If we were about to score a big deal with a major client, but we don't know if we can handle the request in time, given that we have already so many orders in the shop, how can we decide on that? Simulation Time!

Assuming that we know how much time each process takes, and the types of processing each order needs, we can verify when all of our registered orders, together with the new one, will be completed. I know these calculations could be done by hand, (yeah yeah) but bear with me on this one.

Note that I'm not a Production Engineer, don't take my advice on production management. It's just for the sake of the blog post and the use for simulations in our lives.

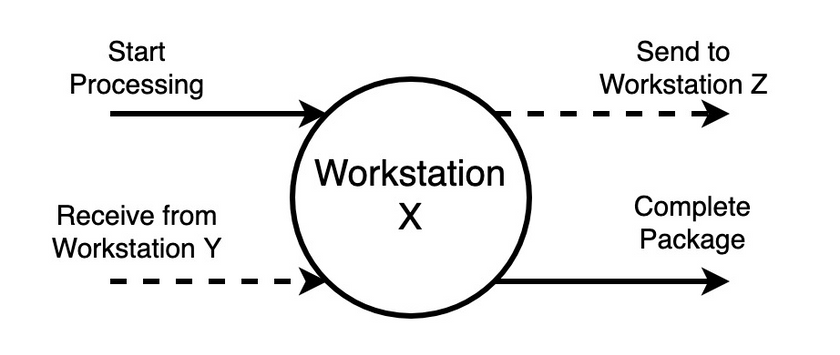

Looking at workstations as if they were picking an order from the pile/queue, "doing their thing" and sending it to the next step, we can think of them as completely individual and independent actors from each other, inside the simulation engine. They simply pick an order from the queue and put it in the next one after the work is done. If nothing is waiting in line, the workstation stops until a new one appears. It can also be the starting or finishing point of an order.

Quick intro to Elixir and Actors

Continuing with the same thought, we identify some Actor Model programming characteristics. In response to a message it receives, an actor can:

- make local decisions;

- create more actors;

- send more messages;

- determine how to respond to the received message.

Actors may modify their private state, but can only affect each other indirectly through messaging. An actor is also a lightweight entity, unlike Operating System processes or threads.

One of the selling points of Elixir is its support for concurrency. The concurrency model relies on Actors. So, implementing the initial idea, where each workstation is an actor part of the simulation, should not be a problem.

Different types of simulations

There are two different types of simulation, Discrete Event Simulation (DES) and Continuous Simulation (CS).

-

DES: It models the operation of a system as a (discrete) sequence of events in time.

-

CES: the system state is changed continuously over time based on a set of differential equations defining the rates of change of state variables.

In our carpentry workshop, events can be treated as discrete. So in our simulation, time "hops" because events are instantaneous (jump straight to finish processing time) and do not occur in a continuous form. This way, the clock skips to the next event moment, each time an event is completed, as the simulation proceeds;

Step by step

Guess the boring talk is over and it's now time to put the ideas into work.

Here, I'll use GenServers, as workstations. With the Erlang and GenServer characteristics, a process has a FIFO "mailbox", ensuring the ordering of the messages received by each workstation. If process A sends messages x and y, by this order, to process B, we know that it'll receive them by the same order.

# Process A send(B, x) send(B, y) # Process B receive() # => x receive() # => y

Though, if we have a process C that also sends a message w to B in the meantime, we don't have guarantees in what order it'll be received. Only that x will be first then y.

# Process A send(B, x) send(B, y) # Process C send(B, w) # Process B receive() # => w || x receive() # => w || x || y receive() # => w || y

Everyone that has already dealt with concurrency problems like this one, with several actors swapping messages, can smell a problem here... We need to have some kind of synchronization between processes. Order of messages from different actors/workstations matters in our simulation. That's why I'm introducing the Simulation Manager. We must ensure that the Manager only fast-forwards the clock when it has all the updated values from the actors affected by some event in the past, keeping "timed events" from overlapping.

This process will ensure synchronization and message order. The existence of a centralized actor simplifies this problem and potentially increases efficiency due to less metadata and extra messages in a peer-to-peer case.

A bit of code

1. To start our simulation, we start a new process (actor). This will be the Simulation Manager and is responsible for spawning an actor for each workstation that composes our workshop's pipeline;

# Simulation Manager code def start_link do actors_pids = CarpentryWorkshop.Workstations.get_all() |> Map.new(fn place -> start_place_actor(place) end) GenServer.start_link( __MODULE__, %{ pids: actors_pids, clock: Timex.now(), events: [], awaiting: [] }, name: SimManager ) end defp start_place_actor(place) do {:ok, pid} = Pipe.SimPlace.start_link(place) {place.id, pid} end

In the code above, we have the Simulation Manager starting all the other actors and storing their pids to identify each one in the rest of the distributed algorithm. Note that there were other alternatives to this in Elixir, but this one is probably the easiest.

Events represent messages received from each place and awaiting are actors that the Manager should wait for before advancing the simulation time.

2. Each of these actors will collect the list of orders in their queue, and sort them by the delivery date. Announcing to the manager when the next event will occur. The next event is calculated by the processing time of the first package in the queue;

# Simulation Place code def start_link(place_id) do events = get_events_list GenServer.start_link( __MODULE__, %{ self_info: place_id, pids: %{}, events: events, } ) next = hd(events) events |> hd |> finish_processing_timestamp send(SimManager, {:next_event, next, place_id} end def get_events_list do place_id |> CarpentryWorkshop. Orders.list_for_place(place_id) |> CarpentryWorkhop. Orders.sort_by_delivery_time(events) end def finish_processing_timestamp do # Based on the type of order # Calculate end processing time end

3. When the manager gets all announcements, orders them, and advances clock time to the next event, warning the actor where the event will occur;

def handle_info({:next_event, event, sender}, state) do ordered = insert_ordered(state.events, event, sender) awaiting = state.awaiting -- [sender] {rest_events, next_step} = send_next_event(ordered, awaiting) ... end # we have all answers def send_next_event(events, []) do next_event = get_first_from_queue(events) send(next_event.place_id, {:advance, event}) end # missing answers from actors def send_next_event(events, awaiting) do {events, nil} end

4. Then, the respective workstation Actor receives a message from the manager and completes the "event" (package processed). If the package is concluded, it will update the database value for the expected delivery time. Else, it will send a message with the package to the next workstation (actor). It also warns the manager, that it needs to wait for the next event update from itself and the next workstation;

def handle_info({:advance, event}, state) do # check if this is the last place for this order case tl(event.rest_path) do [] -> # Update DB Value update_prediction(event) path -> warn_next_workstation(state, event) warn_manager(state, event) end ... end

5. The intervening workstation actor will recalculate the next event time and announce it to the simulation manager (nil in case that there is no package in the queue), to continue the simulation; This part is analogous to Step 2.

6. The simulation stops when the manager doesn’t have more "next events" in the queue.

if rest_events == [] && next_step == nil do # Finished Simulation stop_workstation_actors(pids) {:stop, :normal, []} end

In the code snippets above, the parts for calculating timestamps and the next events are omitted, but they account for a major part of this simulation and synchronization between actors.

After gluing every missing part of this simulation, our workshop is now ready to answer when an order (newly placed or not) will be ready.

Wrapping up

We demonstrated some of the advantages of using Elixir for distributed algorithms/problems. However, use this kind of distributed approach with caution, as it can introduce all sorts of bugs. And believe me, you won't like debugging distributed stuff...

Hope I got you a little bit more interested in simulations in general and taking advantage of the actor model to solve exquisite problems.